How To Use Ulysses¶

Note

This section assumes you have a basic understanding of how a cluster works (see Cluster Basics for a pedestrian introduction) and what are Ulysses’ partitions (see Partitions). Having a look at the Specs Sheet is useful as well, even if maybe not completely necessary.

Note

The cluster has no graphical interface; all operations have to be done via a terminal (this is the norm with clusters). If you don’t know what a terminal is or how to use it, you can have a quick tutorial on Ubuntu’s website: https://ubuntu.com/tutorials/command-line-for-beginners. The tutorial also applies to other Linux distributions, as well as to MacOS.

Step 0: Get an Account¶

If you have a SISSA email, you can enable your account to Ulysses by writing an email to helpdesk-hpc@sissa.it.

If your name is John Doe, your email will probably look like jdoe@sissa.it; in the following, you will need to replace username with your equivalent of jdoe.

Step 1: Login¶

Warning

Ulysses used to be reachable from outside SISSA; however, since the upgraded version is still in beta, it’s temporarily reachable only from SISSA’s internal network. In order to enter the internal SISSA network, you have to connect to SISSA’s VPN: https://www.itcs.sissa.it/services/network/internal/vpnclient. Afterwards, you can access the cluster as explained below.

Warning

frontend1.hpc.sissa.it is still providing access to the old version of Ulysses, but it will be soon redeployed as a login node for the new version of Ulysses. Until that happens, please use only frontend2.hpc.sissa.it to access Ulysses.

Open up a terminal and execute the following command (do not copy the “$”, it’s just there to say that we are executing a shell command):

$ ssh username@frontend2.hpc.sissa.it

Note

If you need to use graphical software on the cluster, replace ssh with ssh -X.

You should be greeted with a welcome message and the terminal should be positioned in your home folder. To check that, executing the pwd command should give you /home/username.

Note

/home/username is meant to store important files, not to run calculations, and it’s backed up daily. The quota you have is 200 GiB.

To move to a place where you can run calculations, execute cd /scratch/username. Here you can create a new folder for you brand new HPC project via mkdir yourfolder. Then move to the new folder with cd yourfolder.

Note

/scratch/username is a parallel filesystem on which you can run calculations, and it’s not backed up. The quota you have is 5 TiB.

Step 2: Load Your Software¶

It’s time to load the software that you’re going to use for the simulation, or to compile your own.

Step 2.1: Using Modules¶

Ulysses’ software is organized in modules. ITCS has a great in-depth documentation on the modules structure, so if you’re not familiar with it please take a look: https://www.itcs.sissa.it/services/modules. Here I’ll just cover the basics.

In a nutshell modules are a great way of handling multiple software or multiple versions of the same software, and they work as a plug-in / plug-out tool; you plug in a certain software to make it available to the system, and when you finish you can plug it out so that it doesn’t interfere with another software you have to use.

Say for example that you want to use Intel’s C compiler, icc. This command, however, is not available by default. So you first determine what modules are available in the system, and whether Intel’s compiler is among them; to do that, you use module avail:

$ module avail

-------------------------- /opt/ohpc/pub/modulefiles ---------------------------

autotools hwloc/2.1.0 llvm5/5.0.1

cmake/3.15.4 intel/18.0.3.222 prun/1.3

gnu8/8.3.0 intel/19.0.4.243 (D) singularity/3.4.1

------------------------- /opt/sissa/modulefiles/apps --------------------------

comsol/5.5 mathematica/11.3 python3/3.6

git/2.9.3 mathematica/12.0 (D) ruby/2.5

git/2.18 (D) matlab/2016b sm/2.4.43

gnuplot/5.2.4 matlab/2018a texlive/2018

idl/8.7 matlab/2018b texlive/2019 (D)

intelpython3/3.6.8 matlab/2019a vmd/1.9.3 (D)

maple/2018 matlab/2019b (D) vmd/1.9.4a12

maple/2019 (D) perl/5.26 xcrysden/1.5.60

----------------------- /opt/sissa/modulefiles/compilers -----------------------

cuda/9.0 cuda/10.0 gnu7/7.3.1

cuda/9.1 cuda/10.1 (D) pgi/19.4

------------------------- /opt/sissa/modulefiles/libs --------------------------

eigen/3.3.7 fsl/6.0.1 libtensorflow_cc/1.14.0

-------------------- /usr/share/lmod/lmod/modulefiles/Core ---------------------

lmod settarg

Where:

D: Default Module

As you see there are 2 versions of the intel module: intel/18.0.3.222 and intel/19.0.4.243. You can load a specific version, for example intel/19.0.4.243, via:

$ module load intel/19.0.4.243

If you instead use the generic module name, intel, the default version (marked with (D)) will be loaded:

$ module load intel

You can check which modules are loaded in your environment by using module list:

$ module list

Currently Loaded Modules:

1) gcc/8 2) intel/19.0.4.243

For example, in this case, loading the intel/19.0.4.243 module automatically loaded the gcc/8 module as well.

It might happen that you’re looking for a specific piece of software but you don’t see it when you use module avail. Let’s say for example that you want to use Intel’s MKL with the GNU compiler. While Intel’s MKL is automatically included in Intel’s compiler module, it has to be loaded as an additional module when usign the GNU compiler. However, the module avail command above shows no traces of an mkl module; but trust me, it’s there.

The infallible way to find modules, even the ones that might be “invisible” by default, is via module spider. It’s a sort of internal search engine for modules; you can look for a possible mkl module via:

$ module spider mkl

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

mkl:

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Description:

Intel Math Kernel Library for C/C++ and Fortran

Versions:

mkl/18.0.3.222

mkl/19.0.4.243

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

For detailed information about a specific "mkl" module (including how to load

the modules) use the module's full name.

For example:

$ module spider mkl/19.0.4.243

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Ok, this tells us that the module it’s there (and there are 2 available versions) but still it doesn’t say how to load it. However, the message is quite explanatory: if you want to receive instructions on how to load a specific version of the module, you have to use module spider again with the specific version you want to load. For example, if we want to know how to load mkl/19.0.4.243:

$ module spider mkl/19.0.4.243

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

mkl: mkl/19.0.4.243

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Description:

Intel Math Kernel Library for C/C++ and Fortran

You will need to load all module(s) on any one of the lines below before the

"mkl/19.0.4.243" module is available to load.

gnu7/7.3.1

gnu8/8.3.0

pgi/19.4

Aha! The message is telling us that if we want to be able to load mkl/19.0.4.243 we have to load one of the 3 listed modules first. Let’s say that we choose to load gnu8/8.3.0; then, if we do module avail again after loading this module, this is what we get:

$ module load gnu8/8.3.0

$ module avail

------------------------- /opt/ohpc/pub/moduledeps/gnu -------------------------

mkl/18.0.3.222 mkl/19.0.4.243 (D)

-------------------------- /opt/sissa/moduledeps/gnu8 --------------------------

gmp/6.1.2

------------------------ /opt/ohpc/pub/moduledeps/gnu8 -------------------------

R/3.6.1 hdf5/1.10.5 mvapich2/2.3.2 openmpi3/3.1.4 scotch/6.0.6

gsl/2.6 metis/5.1.0 openblas/0.3.7 plasma/2.8.0 superlu/5.2.1

-------------------------- /opt/ohpc/pub/modulefiles ---------------------------

autotools hwloc/2.1.0 llvm5/5.0.1

cmake/3.15.4 intel/18.0.3.222 prun/1.3

gnu8/8.3.0 (L) intel/19.0.4.243 (D) singularity/3.4.1

------------------------- /opt/sissa/modulefiles/apps --------------------------

comsol/5.5 mathematica/11.3 python3/3.6

git/2.9.3 mathematica/12.0 (D) ruby/2.5

git/2.18 (D) matlab/2016b sm/2.4.43

gnuplot/5.2.4 matlab/2018a texlive/2018

idl/8.7 matlab/2018b texlive/2019 (D)

intelpython3/3.6.8 matlab/2019a vmd/1.9.3 (D)

maple/2018 matlab/2019b (D) vmd/1.9.4a12

maple/2019 (D) perl/5.26 xcrysden/1.5.60

----------------------- /opt/sissa/modulefiles/compilers -----------------------

cuda/9.0 cuda/10.0 gnu7/7.3.1

cuda/9.1 cuda/10.1 (D) pgi/19.4

------------------------- /opt/sissa/modulefiles/libs --------------------------

eigen/3.3.7 fsl/6.0.1 libtensorflow_cc/1.14.0

-------------------- /usr/share/lmod/lmod/modulefiles/Core ---------------------

lmod settarg

Where:

L: Module is loaded

D: Default Module

Note

Loading the module gnu8/8.3.0 has made available a whole bunch of new different modules that depend on it, in the first three sections that end with moduledeps/gnu or moduledeps/gnu8. These new sets of modules include our original target, mkl/19.0.4.243, but there are also other useful modules such as R, OpenMPI, the HDF5 library or various linear algebra libraries.

This way of searching and loading modules might seem convoluted and overly complicated at first sight, but it’s actually a neat way to keep mental sanity when using module avail. Imagine if all the dependencies of all the modules were made available altogether when using module avail; it would be a neverending list of available modules that would make impossible to spot the one we are looking for. Instead, module avail shows a few “fundamental” modules; then, loading one of them often make additional modules available. In any case, if you have to look for additional modules, module spider is likely to become your new best friend. 😊

Oh, one last thing: if you want to unload a module, just use module unload modulename (for example module unload intel). To unload all the modules at the same time, use module purge.

Step 2.2: Prepare Your Software¶

Depending on your task, the software you need to use for you calculations might be already available as a module or you need to compile it from scratch. In this latter case, refer to the code documentation to find out all the dependencies and load the corresponding modules (or compile the dependencies as well if there are no corresponding modules); then compile the software.

Either way, once your code compiles correctly with all the dependencies you need (and you might want to do a small 5-seconds run just to be sure that there are no missing dependencies at runtime), note down all the modules you’ve loaded in the environment. Just to be more explicit, use module list and copy over a file or a piece of paper, you pick one, all the modules that are loaded. You’re gonna need this list later, so keep it somewhere you can easily find it.

Step 3: Define Your Workload¶

Every good calculation starts by carefully engineering the parameters of the simulations. Not only the “physical” parameters of the problem at hand, but also the technical parameters such as the number of CPU cores you have to use, whether or not use a GPU, the memory needed and so on.

In general, you ask yourself the following questions.

Do you need to do a serial MPI or a parallel MPI simulation?

- For a serial MPI calculation you use 1 node (or part of a node)

- For a parallel MPI calculation you use 1 or more nodes

How many CPUs (i.e. threads, i.e. 2 x number of cores in our case) do you need?

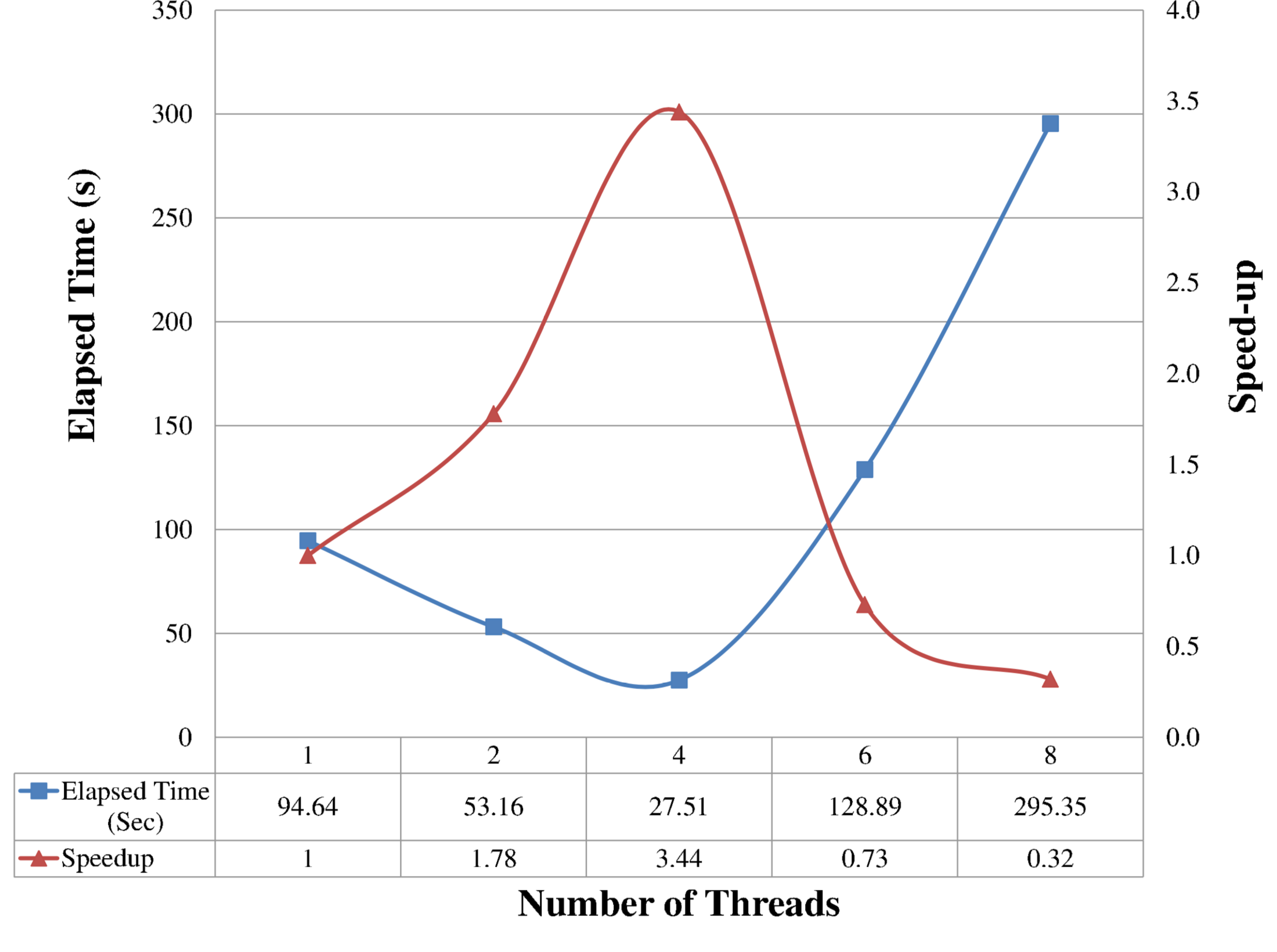

Not a trivial question, as parallelism doesn’t always scale linearly and can saturate after a certain number of CPUs. So don’t blindly ask for all the available CPUs; the best thing to do is to submit some small jobs that do test runs for a variable number of CPUs, and then pick the number of threads that gives the lowest elapsed time (“real” time, not “cpu” time!) or a similar metric. The reason is that, if your software uses multi-core parallelism, you should typically see that time decreases as you increase the number the threads, until at a certain point it stays steady or increases again due to overhead among threads. So the sweet spot for the number of threads is at the minimum of this curve.

Example of elapsed time and speedup vs. number of threads. Image from S.Sankaraiah et al, “Parallel Full HD Video Decoding for Multicore Architecture”,

doi:10.1007/978-981-4585-18-7_36. (C) Springer Science+Business Media Singapore 2014.

(If you do parallel MPI calculations) How many MPI processes do you need?

- You can apply the same reasoning explained above for the number of CPUs.

How much memory (RAM) do you need?

How much disk space do you need? Does it fit into your

/scratchquota?You can check your quota by using the

quotacommand:$ quota /home: XXX of 198GB (hard limit = 200GB) /scratch: XXXX of 4950GB (hard limit = 5000GB)

Please consider that your quota, particularly the

/scratchone, is purely theoretical, as likely there aren’t 5 TB for everybody; so you should also check the overall free space. The 5 TB limit is there so that people that need to perform calculations that store lots of data can do it, but then they should move this data elsewhere; the possibility to store large simulations should be considered temporary.In order to check the overall free space on

/homeand/scratchyou can do:$ df -h /home /scratch Filesystem Size Used Avail Use% Mounted on 10.7.0.43@o2ib,10.7.0.44@o2ib:/home2 76T 11T 65T 14% /home 10.7.0.43@o2ib,10.7.0.44@o2ib:/scrt2 534T 247T 287T 46% /scratch

How much time do you need?

Do you have to do a single calculation or multiple, similar calculations that vary just by a few parameters? If yes, how many of them?

Finding the right balance between all these variables and make them fit into the limits of one or more partitions is your job. It might take a while to get accustomed to it, but it’s practice that makes perfect; so just get your hand dirty! 😊

Note

In general, the less the resources you ask for the faster your calculations will start crunching numbers instead of endlessly waiting in queue. So you have to try to minimize the resources you ask for, while at the same time making sure that your software has the necessary amounts of CPUs, RAM, time, etc. to get the job done.

Once you are done picking up all these parameters, note them down somewhere; you’ll need this info in the next step.

Step 4: Prepare and Send the Job Script¶

It’s finally time for the long awaited job script! Hooray! 🎉

Let’s immediately jump into it and take a look. The script is heavily commented so to help you out, but don’t worry if it’s not all clear at first sight; there’s a step-by-step explanation right after the code block.

You can also download a copy of the job script here: send_job.sh.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 | #!/usr/bin/env bash

#

#

# ==== SLURM part (resource manager part) ===== #

# Modify the following options based on your job's needs.

# Remember that better job specifications mean better usage of resources,

# which then means less time waiting for your job to start.

# So, please specify as many details as possible.

# A description of each option is available next to it.

# SLURM cheatsheet:

#

# https://slurm.schedmd.com/pdfs/summary.pdf

#

#

# ---- Metadata configuration ----

#

#SBATCH --job-name=YourJobName # The name of your job, you'll se it in squeue.

#SBATCH --mail-type=ALL # Mail events (NONE, BEGIN, END, FAIL, ALL). Sends you an email when the job begins, ends, or fails; you can combine options.

#SBATCH --mail-user=user@sissa.it # Where to send the mail

#

# ---- CPU resources configuration ---- | Clarifications at https://slurm.schedmd.com/mc_support.html

#

#SBATCH --ntasks=1 # Number of MPI ranks (1 for MPI serial job)

#SBATCH --cpus-per-task=40 # Number of threads per MPI rank (MAX: 2x32 cores on _partition_2, 2x20 cores on _partition_1)

#[optional] #SBATCH --nodes=1 # Number of nodes

#[optional] #SBATCH --ntasks-per-node=1 # How many tasks on each node

#[optional] #SBATCH --ntasks-per-socket=1 # How many tasks on each socket

#[optional] #SBATCH --ntasks-per-core=1 # How many tasks on each core (set to 1 to be sure that different tasks run on different cores on multi-threaded systems)

#[optional] #SBATCH --distribution=cyclic:cyclic # Distribute tasks cyclically on nodes and sockets. For other options, read the docs.

#

# ---- Other resources configuration (e.g. GPU) ----

#

#[optional] #SBATCH --gpus=2 # Total number of GPUs for the job (MAX: 2 x number of nodes, only available on gpu1 and gpu2)

#[optional] #SBATCH --gpus-per-node=2 # Number of GPUs per node (MAX: 2, only available on gpu1 and gpu2)

#[optional] #SBATCH --gpus-per-task=1 # Number of GPUs per MPI rank (MAX: 2, only available on gpu1 and gpu2); to be used with --ntasks

#

# ---- Memory configuration ----

#

#SBATCH --mem=7900mb # Memory per node (MAX: 63500 on the new ones, 40000 on the old ones); incompatible with --mem-per-cpu.

#[optional] #SBATCH --mem-per-cpu=4000mb # Memory per thread; incompatible with --mem

#

# ---- Partition, Walltime and Output ----

#

#[unconfig] #SBATCH --array=01-10 # Create a job array. Useful for multiple, similar jobs. To use, read this: https://slurm.schedmd.com/job_array.html

#SBATCH --partition=regular1 # Partition (queue). Avail: regular1, regular2, long1, long2, wide1, wide2, gpu1, gpu2. Multiple partitions are possible.

#SBATCH --time=00:05:00 # Time limit hrs:min:sec

#SBATCH --output=%x.o%j # Standard output log in TORQUE-style -- WARNING: %x requires a new enough SLURM. Use %j for regular jobs and %A-%a for array jobs

#SBATCH --error=%x.e%j # Standard error log in TORQUE-style -- WARNING: %x requires a new enough SLURM. Use %j for regular jobs and %A-%a for array jobs

#

# ==== End of SLURM part (resource manager part) ===== #

#

#

# ==== Modules part (load all the modules) ===== #

# Load all the modules that you need for your job to execute.

# Additionally, export all the custom variables that you need to export.

# Example:

#

# module load intel

# export PATH=:/my/custom/path/:$PATH

# export MAGMA_NUM_GPUS=2

#

#

# ==== End of Modules part (load all the modules) ===== #

#

#

# ==== Info part (say things) ===== #

# DO NOT MODIFY. This part prints useful info on your output file.

#

NOW=`date +%H:%M-%a-%d/%b/%Y`

echo '------------------------------------------------------'

echo 'This job is allocated on '$SLURM_JOB_CPUS_PER_NODE' cpu(s)'

echo 'Job is running on node(s): '

echo $SLURM_JOB_NODELIST

echo '------------------------------------------------------'

echo 'WORKINFO:'

echo 'SLURM: job starting at '$NOW

echo 'SLURM: sbatch is running on '$SLURM_SUBMIT_HOST

echo 'SLURM: executing on cluster '$SLURM_CLUSTER_NAME

echo 'SLURM: executing on partition '$SLURM_JOB_PARTITION

echo 'SLURM: working directory is '$SLURM_SUBMIT_DIR

echo 'SLURM: current home directory is '$(getent passwd $SLURM_JOB_ACCOUNT | cut -d: -f6)

echo ""

echo 'JOBINFO:'

echo 'SLURM: job identifier is '$SLURM_JOBID

echo 'SLURM: job name is '$SLURM_JOB_NAME

echo ""

echo 'NODEINFO:'

echo 'SLURM: number of nodes is '$SLURM_JOB_NUM_NODES

echo 'SLURM: number of cpus/node is '$SLURM_JOB_CPUS_PER_NODE

echo 'SLURM: number of gpus/node is '$SLURM_GPUS_PER_NODE

echo '------------------------------------------------------'

#

# ==== End of Info part (say things) ===== #

#

# Should not be necessary anymore with SLURM, as this is the default, but you never know...

cd $SLURM_SUBMIT_DIR

# ==== JOB COMMANDS ===== #

# The part that actually executes all the operations you want to do.

# Just fill this part as if it was a regular Bash script that you want to

# run on your computer.

# Example:

#

# echo "Hello World! :)"

# ./HelloWorld

# echo "Executing post-analysis"

# ./Analyze

# mv analysis.txt ./results/

#

# ==== END OF JOB COMMANDS ===== #

# Wait for processes, if any.

echo "Waiting for all the processes to finish..."

wait

|

Ok, let’s go step-by-step.

Script Format¶

The script is just a regular Bash script that contains the operations you want to perform in the JOB COMMANDS section towards the end.

Comments, in Bash scripts, begin with a #; however, in this case, lines that begin with the comment #SBATCH are special lines that do not get executed anyway by the Bash script, but are parsed by SLURM and interpreted as instructions for the resources you are asking for. Lines that do not begin with that exact sequence of characters, like #[optional] #SBATCH or #[unconfig] #SBATCH, are instead ignored by SLURM and treated just as other regular comments.

Each #SBATCH directive is followed by an option, in the form #SBATCH --option=value (and then by another explanatory comment that I’ve added just for reference). These options are the same options supported by SLURM’s sbatch command The complete list of sbatch options is available on SLURM’s website: https://slurm.schedmd.com/sbatch.html; refer to it for clarifications or more advanced settings.

sbatch is the primary command that you use to queue a calculation. Suppose for a second that you have a regular Bash script with the list of operations you want to do with your software (i.e. containing just the JOB COMMANDS section, nothing else). In principle, you could send this regular script via e.g.

$ sbatch --ntasks=1 --cpus-per-task=40 --mem=7900mb --partition=regular1 --time=00:05:00 ...(other options)... regular_script.sh

However remembering all these options every time you have to send a calculation is a pain in the neck, without adding the fact that you don’t have a trace of all the options you’ve used to send a particular job or set of jobs.

The solution is to collect all these command-line options for sbatch in those special #SBATCH --option=value Bash comments; all those --option=value pairs will then be interpreted just as if they were given to sbatch on the command line.

In other words, if you augment you regular Bash script regular_script.sh with special #SBATCH --option=value lines so it becomes what we are calling job_script.sh, you can then send it to the queue via a simple:

$ sbatch job_script.sh

Yep, as simple as that. Of course, if you realize at the very last moment that you want to add some extra command line option, you can do that directly at the command-line level without necessarily adding it to the job script. However, if you have a stable collection of all the command-line options that you commonly use in a single place, i.e. at the beginning of a job script, you can then copy-paste that script every time you have to send a new calculation and just change the relevant bits.

The script is organized in 4 parts. Do not take it as a sacred division, you are actually free to organise it as you want; I just feel that this division may help to keep it well organized. Now we’ll dive in each part in details.

SLURM Part¶

This is the section that contains the command-line options for sbatch that you want to use. It is further divided in sections, though this division it’s a bit random (e.g. the output and error names maybe belong to the metadata section, but in the end you can move this options as you want).

You will need all the resource requirements you’ve engineered and collected in Step 3: Define Your Workload.

Metadata Configuration¶

Contains the job name and things like email configuration.

-

--job-name=<value> A name for your job. Give a descriptive but short name.

Example:

#SBATCH --job-name=TestJob

-

--mail-type=<value> Whether to send an email when a job begins (BEGIN), ends (END) or fails (FAIL). Other options are ALL or NONE. You can combine options by separating them with commas.

Example:

#SBATCH --mail-type=END,FAIL

-

--mail-user=<value> The address to send messages to.

Example:

#SBATCH --mail-type=jdoe@sissa.it

CPU Resources Configuration¶

Contains how many MPI tasks you need, how many threads, etc.

-

--ntasks=<value> How many MPI processes you need. Set it to

1for “serial” jobs (i.e. that don’t use MPI, but can still use OpenMP parallelism). If you are not sure, set it to 1.Example:

#SBATCH --ntasks=1

-

--cpus-per-task=<value> Number of “CPUs” (i.e. CPU threads) per MPI task. This number is limited by each node capabilities, so the max is 64 threads = 2 x 32 cores on the partitions ending with “2” and 40 threads = 2 x 20 cores on the partitions ending with “1”. The global number of CPUs (threads) that you get is equal to this number multiplied by the number MPI processes you’ve asked for.

Example:

#SBATCH --ntasks=1

-

[optional] --nodes=<value> Number of nodes to ask tor. This is optional, as SLURM can use the previous two options automatically determine the number of nodes to give you.

Example:

#SBATCH --nodes=2

-

[optional] --ntasks-per-[node|socket|core]=<value> Number of MPI processes per [node|socket|core]. These options are used to fine-tune how the MPI processes are distributed among the available resources. If you don’t have a good reason to use it, just don’t use it.

I think that a useful option is

--ntasks-per-core=1, that forces separate MPI processes to run on separate cores in order to avoid possible slowdowns. This automatically happens if Hyper-Threading is disabled, but since it’s enabled on Ulysses2 this option can take care of it. Note that this doesn’t disable Hyper-Threading, and on the contrary the MPI processes can still take advantage of having 2 threads per core. The only difference is that we make sure that each pair of threads belongs to the same core.Example:

#SBATCH --ntasks-per-core=1

Other Resources Configuration¶

Settings for other resources, such as GPUs.

-

--gpus=<value> Total number of GPUs requested for the job. Valid only on

gpu1andgpu2; you can ask at most 2 GPUs for each node you ask.Example:

#SBATCH --gpus=2

-

--gpus-per-node=<value> Number of GPUs per node. Valid only on

gpu1andgpu2; you can ask at most 2 GPUs.Example:

#SBATCH --gpus-per-node=2

-

--gpus-per-task=<value> Number of GPUs per MPI process; intended for use in conjunction with

--ntasks. Valid only ongpu1andgpu2; you can ask at most 2 GPUs.Example:

#SBATCH --gpus-per-task=2

Memory Configuration¶

Memory (RAM) resources. Always specify the amount of RAM you need, otherwise you might encounted unexpected behaviors!

-

--mem=<value> Amount of memory per node. Refer to the table in Partitions for the limits. Incompatible with

--mem-per-cpu.Example:

#SBATCH --mem=7900mb

-

[optional] --mem-per-cpu=<value> Amount of memory per CPU (thread). Default value:

512mb; refer to the table in Partitions for the limits. Incompatible with--mem.Example:

#SBATCH --mem-per-cpu=4000mb

Partition, Walltime and Output¶

This section specifies the partition to use, the requested amount of time and the names of the log files.

-

--partition=<value> Partition (queue) to send the job to. Refer to the table in Partitions for the details. Multiple partitions are possible, separated by commas; the job will then execute on the first partition that has available resources.

Example:

#SBATCH --partition=regular1,regular2

-

--time=<value> The maximum time to be allocated for your job, in

HH:MM:SSformat. Default value:01:00:00; refer to the table in Partitions for the time limits.Example:

#SBATCH --time=12:00:00

-

[optional] --array=<value> Generates and queues multiple copies of the same job, each one having a different value of the environment variable

$SLURM_ARRAY_TASK_ID. The value for this variable is taken from a list that you provide as input, which can be a range (e.g.1-10, optionally with a step e.g.1-10:2) or a list of values (e.g.1,3,17).Useful if you have to run multiple calculations that just differ by the value of some parameters, as you can use the value of

$SLURM_ARRAY_TASK_IDto select a parameter or a specific set of parameters for that simulation.More info and examples: https://slurm.schedmd.com/job_array.html

Example:

#SBATCH --array=0-12:3 # Expands to 0, 3, 6, 9, 12

-

[optional] --[output|error]=<value> Custom name for the output log and the error log. In order to use file names which are compatible with the ones use by TORQUE (the scheduler in Ulysses v1), I suggest to use this form

#SBATCH --output=%x.o%j #SBATCH --error=%x.e%j

for regular jobs and this form

#SBATCH --output=%x.o%A-%a #SBATCH --error=%x.e%A-%a

for array jobs.

%xis a placeholder for the name,%jfor the job ID,%Afor the global array job ID and%afor the array index.This is just a suggestion, you can use the names that you prefer or just don’t specify them in order to use the default ones.

Modules Part¶

This section to be filled with all the modules you’ve collected in Step 2: Load Your Software. Be sure to export the relevant environment variables as well, if needed by your software.

Example (just random stuff to make my point):

module load intel

export PATH=:/my/custom/path/:$PATH

export MAGMA_NUM_GPUS=2

Info Part¶

You don’t need to modify this part; it’s just a section that prints some job info in your output file, nothing more. If you don’t like it, you can safely remove it.

Job Commands Part¶

This is the section that contains the actual things your calculation has to do, so this section is completely up to you.

Before the commands, there’s a line

cd $SLURM_SUBMIT_DIR

that brings the shell into the directory from which you’ve submitted the script. A similar line was necessary with the old TORQUE system, but it should be the default behavior with SLURM. Since you never know, best to make it sure it’s actually this way.

Example (just a template of what your code might do):

echo "Hello World! :)"

./HelloWorld

echo "Executing post-analysis"

./Analyze

mv analysis.txt ./results/

Send and Monitor Your Job¶

At this point, you’re ready to go. You can put your job in queue via (the script is named send_job.sh):

$ sbatch send_job.sh

The command above will return a number identifying the job, called job ID.

The script will be executed in the folder from where you’ve sent it as soon as there are available resources; you can monitor the status of your request for resources via:

$ squeue -j jobid

Or, to view all of your jobs, you can use

$ squeue -u username

You can print more job infos by adding the -l option; as a general tip, I also suggest you to use the screen reader less so not to clog your terminal:

$ squeue -l -u username | less

When you’ve finished taking a look, you can quit the screen reader by pressing the Q key on your keyboard.

For both running jobs and jobs that are already completed, you can print even more detailed infos via (just replace jobid with):

$ sacct -j jobid --format=User,JobID,Jobname,partition,state,time,start,end,elapsed,MaxRss,MaxVMSize,nnodes,ncpus,nodelist

Note

As you’ve noticed, basically all SLURM commands start by “s” and are followed by a term that explain their functions. So “batch” refer to batch jobs, “queue” refer to jobs in queue, etc. In this case “acct” stands for “accounting” information.

Step 5: Get Your Results¶

Once the calculations are completed, you might want to transfer the results (or some post-processed form of the results) to your SISSA workstation or to your laptop. There are 2 command-line based ways to do it:

- Via

scp - Via

sftp

ITCS has a very complete documentation on the usage of scp, so just have a look at it: https://www.itcs.sissa.it/services/network/scp/scp-index. The only caveat is that you have to replace your-SISSA-username@hostname:local_path/file_name with username@frontend2.hpc.sissa.it:path_on_the_cluster/file_name.

As for sftp, there are many tutorials online. You can for example read this one by DigitalOcean: https://www.digitalocean.com/community/tutorials/how-to-use-sftp-to-securely-transfer-files-with-a-remote-server. Again, you just have to replace sammy@your_server_ip_or_remote_hostname with username@frontend2.hpc.sissa.it.

Note

There are also more user-friendly ways to access the files on the cluster, so that you can navigate these files with the default file manager of you operating system as if they were on your workstation or on your laptop. These setups are discussed in the section Explore Files in a User-Friendly Way.